Duke’s psychiatry residency offers three distinct tracks—the Physician Scientist Track, the Clinician Educator Track, and the Duke Psychotherapy Track—for residents interested in developing advanced skills in a particular area during their time in the program.

Each track includes didactics, opportunities to connect with mentors and faculty experts in the track’s focus area, and other targeted resources that help residents gain expertise in their chosen domains.

Heather Vestal, MD, MHS, director of the psychiatry residency training program, explains that the tracks are “extremely flexible” and “are a great way for residents to take a deeper dive in particular areas of interest, in order to further advance their careers.” The tracks are open to all residents in the psychiatry program as well as residents in the combined internal medicine-psychiatry program.

Residents aren’t required to pursue a track, but most do: of the department’s 45 psychiatry residents, 30 of them are part of at least one.

Physician Scientist Track

Led by faculty members Alexandra Bey, MD, PhD, and Jonathan Posner, MD, the Physician Scientist Track (PST) attracts residents with a strong interest in research. “Residents in this track receive protected time in their schedules to conduct research, in addition to still receiving strong clinical training,” Vestal said.

The program offers two PST slots per year, and residents are recruited into the track.

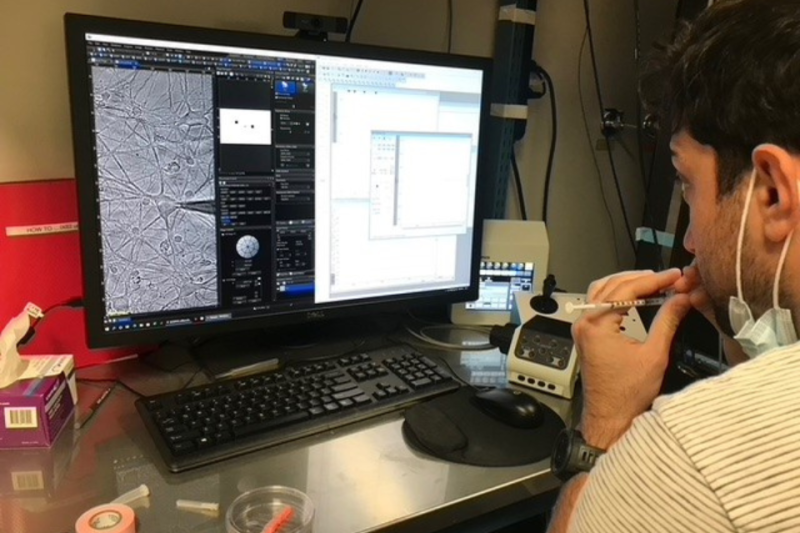

Alexander Moghadam, MD, PhD, a third-year resident in the PST, became interested in psychiatry and research when he was an undergraduate at John’s Hopkins University, where he majored in neuroscience. “I kind of ‘drank the psychiatry Kool-Aid’ as an undergraduate at Hopkins,” Moghadam said. Early on, he joined the Behavioral Neuroscience Group, which exposed him not only to basic neuroscience but also to the school’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

“I went on rounds there. I got really interested in the patients and I said, ‘This is cool. I like neuroscience. I like psychiatry. How can I keep doing this?’” he recalled.

Moghadam studied ingestive behaviors as an undergraduate lab technician and went on to investigate psychosis for his MD/PhD at New York Medical College. He is currently researching targeted interventions and treatments for mental illnesses like schizophrenia. “My goal is to understand how antipsychotics actually work,” he said.

To Moghadam, the PST is unique because of the protected research time it affords residents. “Duke has a great program because they really front-end a lot of time to do research, and that’s not typical. Most programs have it mostly on the back end,” he explained. “That’s a big deal. It’s hard to transition back and forth between clinical work and basic science research.”

The PST had existed informally for many years but became more structured 5 years ago. According to Moghadam, the track prepares residents well for their next steps through significant support systems, a robust curriculum, and a future-oriented focus. “There’s a lot of focus on the timeline getting to the next stage in our career. That could be fellowship, applying for an assistant professorship, or applying for grants,” he said.

Moghadam will continue his neuroscience research next year—his last year of residency—and plans to pursue a geriatric psychiatry fellowship after residency.

Psychotherapy Track

The Duke Psychotherapy Track (DPT) enables residents to gain fundamental knowledge and skills in psychotherapy, including psychodynamics, cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, group therapy, and family therapy. Residents in the track, which is led by associate professor Marla Wald, MD, choose to specialize in one of these areas.

Shelby Powers, MD, a fourth-year resident in the DPT, defines psychotherapy as “treatment in which words and the relationship between two or more people are the means to improve mental health.” She’s intrigued by psychotherapy because, she noted, “people come to us when they are suffering, and it’s not suffering that we have labs or imaging for. I love how you get to learn about people’s stories and the way you can help people change their lives.”

Powers started off wanting to be an ob/gyn physician, but was drawn to psychiatry during medical school, when she participated in a sexual health decision making program for at-risk youth. Also during medical school, her husband suffered a traumatic injury overseas in the Army, which further influenced her decision.

“I just saw so many doctor-patient interactions, and as a family member, it really struck me. My husband is a very resilient person, but they were so worried about him. The psychiatry team always came in and spent a lot of time chatting with him, medical students and residents and attendings,” Powers said. “That gave me an interesting look into psychiatry.”

Her specific interest in psychotherapy developed because she recognized how powerful it was and how many questions she had about it, but how little medical school classes focus on it.

When interviewing for residencies, Powers was looking for a program that provided “more than lip service to psychotherapy.” The DPT was a formal way that she could deeply explore her interests in psychotherapy.

Her favorite part of the track is the journal club. “We get together, read an article, and discuss it with folks who have been practicing in this area for decades in casual dialogue,” she said. “It’s been really valuable.”

Powers plans to pursue an addiction psychiatry fellowship after residency at Yale University, and she hopes to prominently include psychotherapy in her future practice

Clinician Educator Track

The Clinician Educator Track (CET), co-led by faculty members Tara Chandrasekhar, MD, Paul Riordan, MD, and Vestal prepares residents for careers in clinical education. Residents are taught about how to be effective educators and educational leaders, and how to pursue scholarship in medical education.

Vestal established the track at Duke in 2020 because she recognized the sheer number of residents with an interest in education who might benefit from additional opportunities to hone their skills in this area. “In residency there’s just a lot to choose from and plenty of other ways to spend time; interests in medical education can fall to the wayside,” Vestal said. “The track helps residents stay tied to that interest and continue to strengthen it.”

The CET has been extremely popular among the residents, with about 19 residents currently enrolled.

Hania Ibrahim, MD, a third-year resident, joined the CET during her first year of residency, when her clinical responsibilities were keeping her exceptionally busy. She appreciated being able to ease into the track initially. “I got the flexibility to just observe, watch, and learn,” she reflected. “As I evolved and grew, I tailored it to get the resources I needed. There were optional mentorship opportunities. I could lean in as much as I needed to.”

The track offers plenty of opportunities to learn how to teach, including “chalk talks,” where residents give 10- to 15-minute informal lectures and get feedback from peers and mentors.

The CET helps prepare residents for several career paths: “Some of them become faculty [at Duke] and teach the residents who are then in the program,” Vestal said. “Other times, residents go to other programs and they become program directors or other types of educational leaders.”

Ibrahim is interested in pursuing a career in teaching because, she said, “When I teach something, it makes me curious. I push myself to learn more so that I can teach more.”

Learn more about the residency program’s special tracks.