In the past two years, the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers program—known as “NC AHEC”—has helped more than 40 primary care practices across the state implement the collaborative care model, giving patients at those clinics much-needed access to integrated medical and behavioral health care under one roof.

This model, which embeds a behavioral health care manager in the primary care practice and engages a psychiatric consultant for several hours per week, is particularly beneficial to residents in rural areas with few, if any, specialists trained to treat mental health conditions. Developed at the University of Washington’s Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center, the collaborative care model is shown to be financially sustainable, produce better patient outcomes, improve patient and provider satisfaction, and reduce health care costs and disparities.

Facilitating the statewide implementation of this evidence-based model is one of NC AHEC’s latest and most significant initiatives in their 50-year history of recruiting, training, and retaining the workforce needed to create and sustain a healthy North Carolina.

Duke has been part of NC AHEC since its inception in 1974, with Marvin Swartz, MD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, at the helm of Duke AHEC since 1996.

Duke has been part of NC AHEC since its inception in 1974, with Marvin Swartz, MD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, at the helm of Duke AHEC since 1996. Swartz, who helped establish collaborative care in the Duke University Health System in 2014 through a Duke Institute for Health Innovation grant, has made notable contributions to the statewide rollout of the model.

But that’s just one of Duke’s contributions to NC AHEC’s mission. Other endeavors range from coordinating a professional development speakers bureau, to establishing a virtual evidence-based practice center for behavioral health, to supporting community-based clinical placements for trainees in multiple disciplines, to name just a few.

NC AHEC, Duke AHEC & Southern Regional AHEC

Funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) through the University of North Carolina, NC AHEC was established to address national and state concerns with the supply, distribution, and retention of health care professionals. Its initial focus on primary care expanded to include behavioral health care in the 1990s. NC AHEC services and programs include continuing professional development, practice support, and library services for medical professionals and students.

While many states have AHEC programs, Swartz notes that North Carolina is unique in that the state’s General Assembly provides around $50 million annually in supplemental funding, enabling our AHEC programs to pursue a broader scope of activities than those in other states.

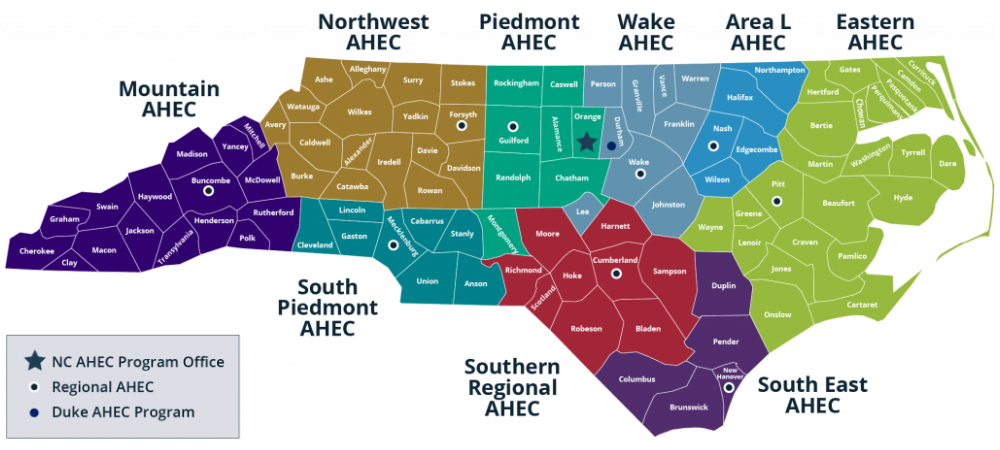

NC AHEC is comprised of nine regional AHEC programs throughout the state and Duke AHEC, which subcontracts with Southern Regional AHEC (SR AHEC) to develop and deliver programs and services primarily in the nine counties surrounding Fayetteville. Sushma Kapoor, MD, a family medicine physician, serves as SR AHEC’s president, CEO, and designated institutional officer.

In addition to providing continuing professional development, practice support, and library services, SR AHEC runs an on-site medical center that serves about 25,000 patients per year. Their services include family medicine, behavioral health, and several specialty clinics.

SR AHEC also offers a family medicine residency program, which Kapoor directs. Kapoor shared that she collaborates regularly with faculty from Duke’s Graduate Medical Education Office and Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, which “brings a lot of value to our program,” she noted.

Supporting the Statewide Collaborative Care Initiative

Swartz partners with SR AHEC faculty and staff on a wide range of AHEC initiatives. As part of the collaborative care initiative, they teamed up with Chris Weathington, NC AHEC’s director of practice support, and Liz Griffin, manager for behavioral health integration at NC AHEC, and a number of collaborative care experts to develop a 20-module online collaborative care model training series.

These free modules augment NC AHEC’s practice support coaching services, which include providing help with best practices, workflows, billing, coding, registry implementation, electronic health record integration, and other areas. J. Nathan Copeland, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, led or co-led the development of several modules.

Swartz also helped plan two recent summits in Raleigh and Fayetteville, designed to help behavioral health care managers learn crucial skills related to collaborative care. In addition, Weathington noted, “Dr. Swartz is heavily involved in providing consultation to our practice support team, and then also, as a psychiatrist, being available to help with clinical questions that come up as we implement the model.”

“Dr. Swartz is heavily involved in providing consultation to our practice support team, and then also, as a psychiatrist, being available to help with clinical questions that come up as we implement the model.”

— Chris Weathington

Professional Development Partnership

Duke also supports SR AHEC in developing and delivering in-person and virtual continuing education programs for nurses, physicians, advanced practice providers, behavioral health clinicians, pharmacists, dentists, and trainees in SR AHEC’s designated region and beyond.

As part of these efforts, Swartz works with Paul Nagy, LCMHC, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke, to coordinate a monthly behavioral health webinar series. Swartz initially recruited Nagy, a clinician who specializes in substance use disorder treatment, to develop and deliver programs related to his work in that area. Over time, partly through engagement with health care providers in the community, Nagy and Swartz expanded the offerings to include a comprehensive range of behavioral health topics.

“Together [with community providers], we were able to identify opportunities to address certain workforce development needs that were inhibiting communities from being all they wanted to be in service to people experiencing these different mental health issues,” Nagy reflected.

While many Duke Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences faculty have presented sessions, Nagy and Swartz also recruit speakers from other universities and community-based practices.

Nagy notes that they aim to provide training that goes beyond merely delivering information. “I think the AHEC approach has always been intended to help professionals practice with a greater sense of efficacy and capacity for achieving optimal patient outcomes,” he said.

“One of our main goals is to keep our graduates in the state, so we’re trying to create linkages across the psychiatry programs and fellowship among trainees and psychiatrists across the state.”

— Marvin Swartz, MD

A key audience for these programs, said Swartz, is psychiatry residents across the state. “One of our main goals is to keep our graduates in the state,” he said, “so we’re trying to create linkages across the psychiatry programs and fellowship among trainees and psychiatrists across the state.” In addition, he noted, some of the state’s newer psychiatry residency programs—which have a narrower range of institutional expertise—rely on these professional development offerings to help fulfill residency didactic requirements.

In addition to working with Nagy to respond to requests for mental health programs, Swartz also fields ongoing requests from AHECs on topics in a variety of primary care disciplines, including family medicine, medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics.

Duke AHEC/SR AHEC Special Projects

Over the years, Duke AHEC and SR AHEC have also partnered on a number of special projects, including but not limited to:

- Working with partners across the state to increase awareness of psychiatric advance directives among clinicians and provide guidance on helping patients complete them (funded by the Duke Endowment)

- Developing the North Carolina Evidence Based Practices Center to support quality behavioral health services by offering customized training, consultation, technical and other assistance (funded by the Duke Endowment)

- Helping health professionals develop cultural competency, with a focus on building Spanish language and Spanish medical interpretation skills (funded by the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust)

- Offering a certification course, led by Swartz, to train physicians to become involuntary commitment examiners (professionals who assess whether a patient needs to be admitted to inpatient psychiatric care involuntarily) (funded by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services)

- Training primary care clinicians on evidence-based practices to screen patients for substance use disorders (funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

- Engaging employees of churches, law enforcement, judicial system, social service agencies, public schools, and other community organizations in addressing the problems of substance use disorders and opioid addiction (funded by the Cumberland Community Foundation; facilitated by Nagy in partnership with SR AHEC)

Local Duke AHEC Initiatives

In addition to his collaborative work with SR AHEC, Swartz oversees several Durham-based Duke AHEC initiatives.

Through its Health Careers and Workforce Diversity program, Duke AHEC engages elementary, middle, and high school students in a variety of awareness, mentoring, and education programs to support students academically and expose them to the knowledge and skills needed in health care fields.

For example, Duke AHEC partners with the City of Medicine Academy (CMA), a charter high school in Durham, to host ninth and tenth grade students for afterschool information sessions on the Duke University Health System campus. Another Duke AHEC/CMA program pairs rising seniors with a Duke health care provider to shadow and learn about their respective discipline.

Duke AHEC also supports community-based clinical training rotations for primary care and psychiatry residents, medical students, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. Psychiatry placements include Lincoln Community Health Center, El Futuro, Triangle Residential Options for Substance Abuse (TROSA), and the Durham County Detention Facility.

Reflecting on a Rewarding Opportunity

Having led Duke AHEC for more than half of its 50 years, Swartz is grateful for the opportunities he’s had to help enhance the health care workforce across the state and develop relationships with people he wouldn’t have crossed paths with in his everyday work as a Duke psychiatrist.

“I get to do stuff that I identify with and that I feel good about. It’s very gratifying to see our faculty doing great work and being able to have a budget to support these important initiatives,” he reflected.

Want to learn more about Southern Regional AHEC’s 50-year history? Check out their anniversary feature, “Celebrating 50 years of Health and Healing,” by visiting their website and watching their highlights reel: