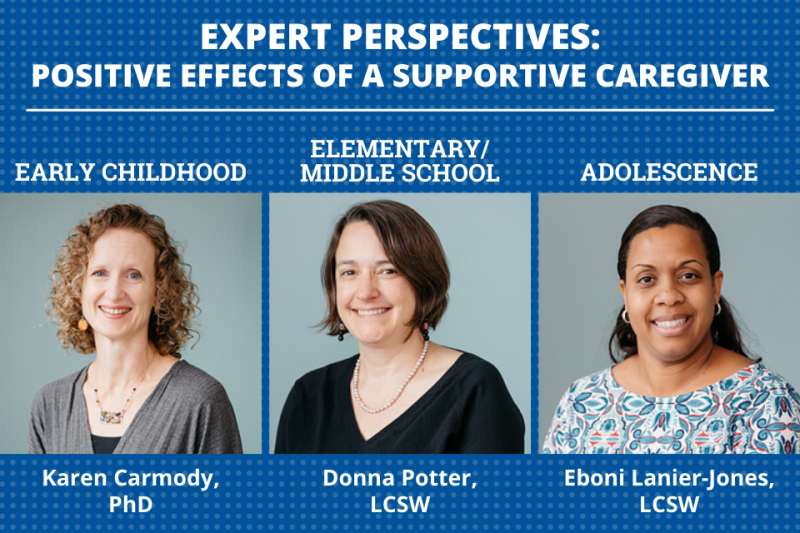

In honor of Children’s Mental Health Awareness Day, we talked with three experts in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences to learn more about the long-ranging positive effects of supportive caregiver relationships on a child’s mental health, well-being and success in life. Meet our experts:

Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers: Karen Carmody, PhD, is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the director of early childhood prevention programs at the Center for Child and Family Health (CCFH). She oversees three evidence-based home visiting programs for parents and families in the Durham area and provides clinical supervision, education and training.

School-Aged Children: Donna Potter, LCSW, is an instructor in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and is the lead clinical faculty member in the North Carolina Child Treatment Program, based in the CCFH. This program trains community clinicians across North Carolina to provide evidence-based treatment in their own communities to children who have experienced trauma.

Adolescents and Teens: Eboni Lanier-Jones, LCSW, provides therapy to children and families and trains clinicians on an group treatment model designed to help adolescents problem solve and improve communication and coping skills through CCFH. She also provides mental health consultation at Southern High School in Durham through a wellness center operated by the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health in the Duke School of Medicine.

Below are some key excerpts from our conversation, edited for length.

What types of connections and relationships are important for children’s mental health and well-being?

Karen Carmody: Research demonstrates that the relationships that you build with those first primary caregivers in your first year of life—like your mom, dad, maybe a grandparent—set the stage for your relationships in the rest of your life. Within those very close relationships, you learn a lot about yourself. You learn that you’re important and that the world responds to you. You learn that relationships are trusting and good places to be, and because of that, you want to go out and build more relationships.

Those relationships are critical, but close relationships with other people beyond of those primary caregivers—a child care teacher, an aunt or a neighbor—can also positively affect children’s emotional and social development over time. And early childhood has a special significance. The relationships that happen in those early childhood years do carry forward and make a difference, even over and above the relationships that are formed later. That said, our experiences throughout life contribute to us being able to succeed as adults, so if someone didn’t have a good experience with a supportive caregiver in early childhood, it is possible to make up for those negative experiences through other healthy relationships over time.

Donna Potter: The most important relationship in any child’s life is their primary caregiver—typically, but not always, the parent(s). Ideally, kids are starting out with this relationship in infancy, and that same relationship carries them all the way through their lives. The more stable and predictable that relationship is from the beginning, the better outcomes we see in kids.

What we’re looking for in these relationships is someone who can consistently be sensitive to a child’s signals for what they need, be present for the child physically and psychologically, make positive attributions about their behavior and provide structure for them to have their own success. As the child ages and their environment expands, we don’t want to see parents who are completely uninvolved, but we also don’t want to have parents who are so involved that the child doesn’t have the opportunity to do what they need to do to grow and learn.

Eboni Lanier-Jones: Adolescents look to their peers, but they also look to solid, supportive caregivers—their parent, a teacher, a school counselor, a coach, a mentor or someone else who’s providing emotional support and giving space for the adolescent to ask questions, bounce ideas off of and maybe seek advice on some things as they’re navigating their world. Sometimes there may be something going on and they can’t talk to a parent, but they can connect with another supportive caregiver. These are the kinds of relationships that really help adolescents grow and thrive.

What are some of the ways caregivers can support children in their development and promote their well-being?

Carmody: The idea of “serve and return connections”—like when a child smiles at you and you smile back—is key. These day-to-day interactions that get repeated and repeated over time are actually making those strong neural connections in the brain that then chart the course for later development.

And being a sensitive and responsive caregiver is critical. One example of this is “following the lead”—like if a child is smiling at you and holding up a toy, rather than trying to teach them by saying, “Oh, that’s a red toy,” you can just engage with them and what’s bringing them joy in the moment, and return that joy back to them. Following their lead helps them to see how important they are in the world and know that they matter to you.

Potter: The importance of routine—and especially bedtime routine—can’t be overstated. Kids in elementary and middle school have all of this brain growth going on. Your brain grows when you sleep, so if you’re not sleeping well, you’re compromising your brain growth. So promoting kids getting to sleep every day at the same time and waking up every day at the same time, and getting enough sleep (minimally eight hours, but ideally 10 to 12 hours) is critical.

And then making sure they’re getting outdoors every day. Lots of research shows being outdoors improves sleep, and that the more time people spend outdoors, the happier they are.

It’s also important to help children develop a good grasp on their feelings and learn to use words to identify their emotional states. One strategy is to recount a situation with a child, tell the child what you observed about their body language in reaction to that situation (e.g., I saw you frown, I saw your shoulders slump) and then offer some possibilities of what they might be feeling (e.g., I’m wondering if you might be feeling angry/frustrated/sad). This emotional coaching can really help a kid feel validated and prevent emotional states from escalating.

Lanier-Jones: It’s important to give teens the opportunity to share things they’re struggling with or worried about, and really allow them to open up and discuss things that may be on their mind. Supportive caregivers should be warm and welcoming and validate the teen’s feelings as much as possible. It’s about keeping communication open and not judging them.

Teens need to be able to trust that they won’t be punished for telling you what’s on their mind and that you won’t share their business with others. If they’re concerned about that, you’re not going to get accurate or honest information, and they may shut you out and look for another person who’s going to give them that validation. Nurturing matters. Connection matters. A level of trust and protection matters.

In what ways does having a supportive caregiver foster children’s mental health and well-being?

Carmody: In addition to promoting overall positive mental health, these close relationships in early childhood can help children develop self-regulation. When kids come into the world, they don’t know how to process all the inputs, but through those relationships, they’re learning how to manage their feelings and how to deal with the world. By the time they’re in preschool, those kids who have had those positive relationships are also able to better manage their behavior in a classroom. They can sit still longer, and they’ve learned how to communicate with other people and manage their big feelings.

Potter: When you have caregivers who are doing some those behaviors I mentioned earlier, those children are more likely to have more secure attachments, and children with secure attachment relationships have better peer relationships and do better in school.

And the better the relationship a child has with that primary caregiver, the more of a buffer that relationship can be against all of the big issues kids are dealing with as they’re trying to go through the developmental stages and have success.

Lanier-Jones: We tend to see those kids having healthy relationships with others, because they’re experiencing that with a caregiver; the modeling piece is important. They have healthy communication patterns and styles, and they understand how to build trust in relationships. They feel supported and they know they’re not alone—they know that someone has their back.

What go-to resources would you recommend for parents, caregivers and school personnel?

Carmody:

- Zero to Three website

- Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families, from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University

- Pandemic Parenting website

Potter:

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network resources for families

- Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child, by John Gottman

- Parenting from the Inside Out, by Daniel Seigel

Lanier-Jones:

- American Psychological Association (APA) Help Center

- Sexual Health Initiative for Teens (SHIFT)

A few other resources for parents, caregivers, mental health professionals and school personnel:

- What You Should Expect from Treatment: Building Stronger Parent-Child Relationships, from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Building Relationships as a Foundation of Trauma-Informed Practices in Schools, from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Connections Matter website