Going to the doctor can be stressful for anyone. All that poking and prodding, the lab work, and the concern that brought you to the clinic in the first place can combine to make even a regular checkup a taxing experience.

Now imagine arriving for that same clinical visit with the unique sensitivities and needs that can accompany an individual on the autism spectrum.

Sam Brandsen, PhD, research analyst with the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development and an autistic individual who parents an autistic child, has done a lot of thinking about medical care for neurodivergent people.

“These patients often put off seeing the doctor unless there’s an absolute emergency. With my child, we’ve had situations where the doctors wanted to run tests, but no one knew how to adapt them in a sensory-friendly way, so the tests weren’t done.”

— Sam Brandsen, PhD

“Persons on the spectrum can have good experiences with doctors, but they can also have very difficult experiences,” he says. “These patients often put off seeing the doctor unless there’s an absolute emergency. With my child, we’ve had situations where the doctors wanted to run tests, but no one knew how to adapt them in a sensory-friendly way, so the tests weren’t done.”

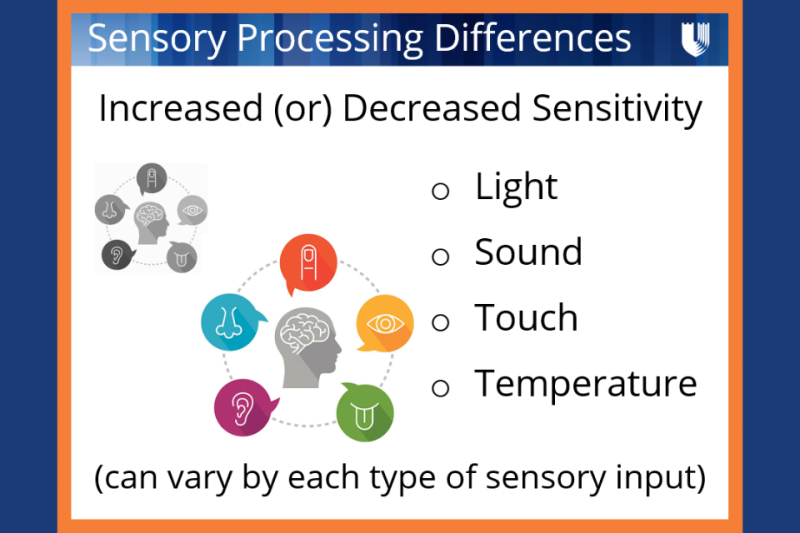

Brandsen decided to tackle the problem from the inside out. He coordinated a panel discussion featuring speakers on the spectrum who shared their experiences of seeking medical care. Multiple departments participated, including occupational therapy, speech therapy, and athletics. Following the panel, Brandsen worked with a team from Duke Health to develop an “Essentials for Autism” training module for providers: case studies, interactive components, and short online sessions designed to help clinicians provide a supportive environment for autistic patients. Topics include how to increase predictability and structure to a patient visit, how to help a patient who becomes overwhelmed, and how to make the clinic a calmer sensory environment.

“I’m excited that the module is out there,” Brandsen says. First piloted among nurses in pediatrics, the training materials could be offered more broadly at Duke Health in the future.

“Essentials in Autism” is just one of multiple efforts underway at the Duke Center for Autism to help physicians and other Duke Health clinicians provide care for persons on the spectrum.

“The ability to complete a basic physical exam on an autistic child is difficult. Physicians often haven’t been trained to use different communication modalities, sensory issues, and unique information processing styles.”

— Gary Maslow, MD, MPH

“The ability to complete a basic physical exam on an autistic child is difficult,” says Gary Maslow, MD, MPH, medical director of the center. “Physicians often haven’t been trained to use different communication modalities, sensory issues, and unique information processing styles.”

To tackle these gaps, the team is building multidisciplinary partnerships, coordinating care for neurodivergent persons across the research, training, and clinical enterprises.

Tara Chandrasekhar, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, leads neurodiversity trainings in the medical management arena and the diagnosis and testing space. Medical students, psychiatry residents, post-graduate research fellows, and psychology interns and externs all rotate through her Friday morning clinic.

“Building synergy for neurodiversity across our research mission is key,” she says, “alongside clinical services and training or workforce development. We try to be mindful and intentional about how to help patients access care and make the latest information available to anyone who’s seeking it.”

The demand for such services is growing. Emergency departments are especially important, with both children and adults on the spectrum sometimes seeking care in these settings. When a neurodivergent patient presents at the emergency department and needs a consult or has complicated medical needs, clinicians will reach out to the team at the Duke Center for Autism for coordinated support with behavioral planning, psychopharmacological evaluations, referrals, and more.

“If a particular need emerges through the emergency department that requires a coordinated response, we are ready. We can leverage our research expertise to help us do a little bit more. It’s amazing that we have this resource and can use it throughout the Duke Health System.”

— Tara Chandrasekhar, MD

“We all work closely together,” Chandrasekhar says. “If a particular need emerges through the emergency department that requires a coordinated response, we are ready. We can leverage our research expertise to help us do a little bit more. It’s amazing that we have this resource and can use it throughout the Duke Health System.”

And not just at Duke alone. Thanks to a unique partnership initiated by Duke in 2016, today the North Carolina-Psychiatry Access Line (NC-PAL) has developed a partnership with the University of North Carolina, the state of North Carolina, and the Department of Health and Human Services to provide free telephone consultation and education to primary care providers (PCPs) navigating the behavioral health needs of pediatric patients, including autistic children.

Nicole Heilbron, PhD, associate professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, says that NC-PAL helps meet a need for specialized behavioral health care in rural communities.

“There are not enough child psychiatrists to care for all the children who might need services,” she says, “including those diagnosed with autism. Our primary care providers are doing a ton of heavy lifting. Thanks to this program, any PCP across the state can call, speak to a social worker and child and adolescent psychiatrist, and consult about a patient. We’re able to provide phone support and connections for further services.”

And while demand still clearly outpaces supply, momentum for improving medical care for autistic patients is building—both at NC-PAL and across Duke Health as a whole.

“Rather than seeing the autism center and the clinic as separate, siloed entities, we emphasize synergy and collaboration,” says Heilbron. “For families and patients who come through our doors at Duke, we don’t want them to have to call five different clinics to find out what to do. We want them to have one call. We want them to be able to focus on what’s important. That’s why we’re doing this work.”